The names you recognize may be costing you money. New research shows investors pay a measurable premium for the comfort of a familiar label. And the pattern extends to fund families and star managers whose track records rarely survive statistical scrutiny.

Walk into any pharmacy and you'll face a choice. On one shelf: Advil, in its familiar orange box. On the other: ibuprofen, the generic, at a fraction of the price. Same active ingredient. Same dosage. Same FDA approval. The only difference is the name on the label. And the 80% markup that comes with it.

It's the same with investing. The instinct that makes Advil feel safer than ibuprofen makes Goldman Sachs or J.P. Morgan feel reassuring. The logic that draws us to Fiji Water draws us to star managers we've seen in headlines.

This isn't stupidity. It's human. Our brains are wired to trust the familiar, and in most of life that shortcut serves us well. In investing, it can cost us a fortune.

What the Research Reveals

A paper published by The Wharton Pension Research Council in November 2025 showed participants two identical S&P 500 index funds. Same holdings, same fees. The only difference was the label: one fund associated with a well-known financial organization, the other with an unfamiliar name.

Participants allocated 65% of their portfolios to the well-known fund. Just 35% to the identical alternative. They estimated the unfamiliar fund carried five to seven percentage points higher probability of loss. They expected lower returns, for essentially the same product.

Here's the uncomfortable part: the bias doesn't disappear with wealth or sophistication. Kostovetsky and Warner (2020) found that financial advisors managing money for wealthy clients showed "particularly strong preferences for brand name benchmarks." The people paid to know better exhibited the same pattern.

Weber, Siebenmorgen, and Weber (2005) showed that familiarity reduces perceived risk regardless of actual risk characteristics. We don't analyze the unfamiliar fund and conclude it's riskier. We feel it's riskier. The analysis comes later, if at all, and usually just confirms what we already believe.

The star manager phenomenon is particularly telling. Investors assume impressive three- or five-year returns demonstrate persistent skill. The SPIVA Persistence Scorecard tells a different story: none of the top-quartile domestic equity funds as of December 2020 remained in the top quartile over the following four years.

The Performance Gap

IFA's Deeper Look research series compares active funds from major fund families against their benchmarks, accounting for survivorship bias and testing for statistical significance using a t-statistic threshold of 2.0. (A t-statistic measures whether results are likely due to skill rather than chance.) The results are remarkably consistent.

Goldman Sachs: 69% of 97 funds underperformed or didn't survive. Just 1% achieved statistically significant outperformance.

Morgan Stanley: 88% of 163 funds underperformed.

Invesco: 85% of 320 funds underperformed.

Franklin Templeton: 75% of 246 funds underperformed.

T. Rowe Price: 62% of 120 funds underperformed.

Even Vanguard's actively managed funds follow the pattern. Despite the firm's reputation for low costs, 63% of its 87 active funds underperformed. Not a single one produced statistically significant alpha.

The survivorship problem makes this worse. An investor looking at a fund family's current lineup sees only the winners. The losers have disappeared, their track records erased.

The Cost of Being Famous

One of the reasons why familiar names underperform is that their business model is built around gathering assets. That's what fund companies are rewarded for, not how well their products perform. A fund that balloons from $1 billion to $10 billion generates ten times the fee revenue regardless of whether it beats its benchmark.

Generic ibuprofen costs less than Advil partly because the generic manufacturer doesn't run expensive ad campaigns. The savings get passed to consumers. But fund companies operate on the inverse principle. The more recognizable the name, the more the company has spent making it recognizable. And someone has to pay for that spending.

Goldman Sachs doesn't maintain offices in every major financial center because it improves returns. Morgan Stanley doesn't advertise during golf tournaments because it helps portfolios. These expenditures serve one purpose: convincing investors to hand over money so the firm can collect fees.

William Sharpe laid out the arithmetic in 1991. Before costs, the average actively managed dollar must equal the average passively managed dollar. Both groups collectively own the entire market. After costs, the average actively managed dollar must underperform by exactly the amount of its costs. This isn't theory. It's arithmetic.

Investors who pay for well-known active funds aren't paying for better investment management. They're paying for the privilege of recognizing the name on their statement.

What to Trust Instead

Evidence-based investing means trusting process and research, not brand recognition.

Instead of asking "which name do I recognize?" the evidence-based investor asks "what does the data show?" Which factors drive returns across decades of research? What costs am I actually paying? Does my advisor have a legal obligation to act in my interest when recommending funds to invest in?

IFA structures client portfolios using Dimensional Fund Advisors as an external fund manager. Most investors have never heard of Dimensional. The firm runs no consumer advertising. Its name doesn't appear on stadiums or in Super Bowl commercials.

None of this guarantees superior returns. Nothing can. But consider the contrast: a firm that gathers assets through advertising must charge fees to cover that advertising. A firm that gathers assets through academic credibility faces no such constraint. The cost savings flow through to investors.

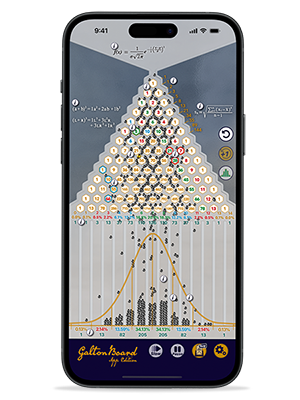

Mark Hebner, founder of Index Fund Advisors, describes his first visit to Dimensional's offices in the 1990s. He saw bell curves on the walls instead of stock tickers. People discussed factor research rather than market predictions. That experience crystallized the foundation of IFA's approach: the difference between investing based on evidence and investing based on speculation.

Questions Worth Asking

A few questions can reveal whether you're paying for brand recognition or receiving genuine value.

What is the fund's total expense ratio? What percentage of this firm's funds have outperformed over the long term? How many funds has the firm closed over the same period? Can the fund company explain its process without referencing past performance or star managers?

Ask your financial advisor, Are you a fiduciary? A fiduciary advisor must act in your interest. A non-fiduciary must merely avoid selling something unsuitable. The difference is enormous.

Also ask them, Why do you use the funds you use? "We use these funds because they provide systematic exposure to factors supported by decades of research at low cost" is a far more reassuring answer than "we use Goldman Sachs because they're a trusted name."

Look for warning signs: heavy emphasis on recognizable names, reluctance to discuss costs, inability to explain the approach in plain terms, confidence in predictions about which managers will outperform.

The Right Kind of Trust

Back to the pharmacy. You know Advil and ibuprofen are the same. You know the price difference pays for advertising, not better medicine.

The investment version is harder to see. The packaging is more sophisticated, the marketing more polished. Goldman Sachs sounds like it should outperform. The star manager on the magazine cover sounds like someone who has figured out what the rest of us haven't.

But the evidence tells the same story the pharmacy tells. The premium buys marketing, not results. The track record that looks like skill is usually luck that hasn't yet run out.

This doesn't mean trust is irrelevant. Trust matters enormously. Most investors are just trusting the wrong things.

Trust evidence over intuition. Trust process over personality. Trust fiduciary duty over brand recognition.

That's the beginning of a different kind of confidence.

Resources

- Agnew, J., Gropper, M. J., Hung, A., Montgomery, N. V., & Thorp, S. (2025). The effects of organizational trust on investors' expectations and allocations. Pension Research Council Working Paper.

- Kostovetsky, L., & Warner, J. B. (2020). Measuring innovation and product differentiation: Evidence from mutual funds. Journal of Finance, 75(2), 779-823.

- Weber, E. U., Siebenmorgen, N., & Weber, M. (2005). Communicating asset risk: How name recognition and the format of historic volatility information affect risk perception and investment decisions. Risk Analysis, 25(3), 597-609.

- Sharpe, W. F. (1991). The arithmetic of active management. Financial Analysts Journal, 47(1), 7-9.

- S&P Dow Jones Indices. (2024). SPIVA U.S. Persistence Scorecard: Year-End 2024.

ROBIN POWELL is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the Editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only.

DISCLOSURES: