Investors often focus on quarterly earnings calls and analyst upgrades while often ignoring three centuries of evidence that suggests their strategy faces mathematical headwinds. The principles illustrating active investing's challenges aren't obscure academic theory — they're the same fundamental discoveries that underpin weather forecasting and quantum mechanics.

Every day, millions of investors make decisions based on recent performance, hot tips, and market timing strategies. Probability theory (the branch of mathematics that governs randomness, risk, and uncertainty) suggests that the core strategies of active investing may be difficult to sustain based on mathematical principles.

These concepts are widely accepted in mathematical theory.

From 1654 through the 20th century, mathematicians established rigorous proofs about how randomness works, how large samples behave, and what constitutes genuine skill versus dumb luck. These proofs provide compelling mathematical support for why passive investing tends to outperform active strategies over time.

Five persistent myths about investing survive despite centuries of mathematical evidence to the contrary. Each myth crumbles under scrutiny from probability theory. Together, they represent active investing's entire intellectual foundation, and that foundation is built on sand.

Myth 1: You Can Profit from Market Timing

The myth sounds reasonable: avoid crashes, capture rallies, sit in cash during downturns. Tactical allocation. Protecting capital. Getting out at the top, getting back in at the bottom. Tens of thousands of newsletters, advisors, and fund managers sell variations on this theme.

Jakob Bernoulli, a 17th-century Swiss scholar who published Ars Conjectandi posthumously in 1713, established mathematical principles that explain why this strategy is so problematic. His Law of Large Numbers established a fundamental truth: individual outcomes are random and unpredictable, but large samples converge reliably to their true average.

Here's what that means for investing. A stock's price movement tomorrow is effectively random because it reacts to news, and news is by definition unpredictable. Whether the market rises or falls on any given day, week, or month tells you nothing about what comes next. Short-term results are noise. But over hundreds or thousands of days (over years and decades) returns converge toward their expected average.

Historical data from 1928 through 2023 appears consistent with Bernoulli's mathematical principles. According to Nasdaq analysis, the S&P 500 generated positive returns in 682 out of 1,152 months, meaning roughly 59% of the time on a monthly basis. Those odds aren't much better than a coin toss. But as the holding period lengthens, the probability of positive returns improves dramatically. Analysis of rolling periods shows that the S&P 500 has delivered positive returns over 100% of all 20-year periods since 1928, meaning the U.S. stock market has never declined over any 20-year period in any reviewed history.

Mark Hebner puts it bluntly in Step 4 of his award-winning book, Index Funds: The 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors: "The problem, however, is finding the crystal ball that can forecast the 40 worst performing days out of 5,036 days". The oft-cited statistic about missing the market's best days works equally well in reverse. Market timers also miss the worst days. But you can't have one without risking the other, and the mathematics proves you can't predict which days will be which.

Historically, time in the market beats timing the market. The longer your holding period, the more the Law of Large Numbers works in your favor, transforming daily randomness into decadal predictability. As Hebner explains in Step 11, "as the period length increases, the median return changes very little, but the range of returns narrows considerably. We refer to this as the benefit of time diversification of returns."

Myth 2: Stock Picking Identifies Future Winners

The second myth is similarly seductive: through diligent research, careful analysis, and pattern recognition, skilled investors can identify undervalued securities before the market catches on. Find the next Amazon. Spot the value trap before it springs. This is the glamorous heart of active investing, the stock picker as financial detective.

In 1654, two French mathematicians, Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat, conducted a correspondence about a gambling problem that founded probability theory. Their breakthrough was calculating expected value: the probability-weighted average of all possible outcomes. This seemingly simple concept undermines the logic of stock picking.

Expected value works like this: if you have a 50% chance of winning $100 and a 50% chance of losing $90, your expected value is (0.5 × $100) (0.5 × -$90) = $5. Positive expected value makes sense. But what's the expected value of stock picking in efficient markets?

Zero. Or more precisely, negative after costs.

Here's why. When millions of participants continuously analyze the same publicly available information (earnings reports, industry trends, management quality, macroeconomic conditions) that information gets embedded into prices almost instantly. As Mark Hebner observes in Step 3 of his book, "Stock pickers don't realize that virtually all of the information and forecasts about a stock, a sector, or an economy is quickly digested by the totality of market participants and swiftly embedded into the price."

The market price represents the consensus probability-weighted estimate of all possible future outcomes. When stock pickers claim a stock is "undervalued," they're claiming to know something millions of other participants don't, despite analyzing the same public information.

Consider a stock trading at $100. If it's truly undervalued at $120, why hasn't the market already bid it up? Because if professional investors genuinely believed it was worth $120, they'd buy it immediately, driving the price to $120. The current price of $100 already incorporates the collective wisdom of all participants. Hebner frames it simply: "If there are many willing buyers and sellers, by definition, it is a fair price."

Fair prices yield expected returns proportional to risk. You can choose higher risk for higher expected returns (small caps, value stocks, emerging markets), but you cannot exploit mispricing through stock picking. The expected value of stock selection skill is generally considered close to zero in efficient markets. Add fees, transaction costs, and tax inefficiency, and the expected value turns decisively negative.

Even if a stock picker achieved a 60% win rate (impressively above random) the mathematics still works against them. A 60% win rate means 40% losses. After transaction costs, taxes on short-term gains, and the opportunity cost of cash drag, the expected value remains negative.

Myth 3: Outperformance Proves Manager Skill

But what about managers who do beat the market? Surely consistent outperformance demonstrates genuine skill, not luck?

This is where Andrey Kolmogorov enters the story. The Russian mathematician placed probability theory on rigorous axiomatic foundations in 1933, making it a respectable branch of mathematics. His work established that randomness isn't chaos; it's mathematically definable, quantifiable, and testable.

Kolmogorov's framework allows us to distinguish skill from luck through statistical significance. The question isn't whether a manager beat the market; it's whether they beat it by enough, over a large enough sample, with consistent enough results, to conclude that skill (not chance) caused the outperformance.

The tool for this is the t-statistic. A t-stat of 2 or greater gives you 97.5% confidence that positive alpha represents genuine skill. Anything less is statistically indistinguishable from luck. Hebner is unequivocal about the importance of t-stats In Step 5 he writes: "Don't trust an alpha or average return without one").

Here's the devastating reality: very few managers meet this threshold. A manager who beats the market by 1% annually for five years might sound impressive. But five years is approximately 60 monthly returns, a tiny sample statistically. With typical return volatility, you'd need far longer periods and far larger outperformance to reach statistical significance.

The mathematics exposes what Hebner calls speculation masquerading as skill. Nobel Laureate Merton Miller captured this perfectly: if 10,000 people try to pick winners, one will score by chance alone. That person becomes a "guru," lionized by the financial media, managing billions based on luck misidentified as skill.

Consider the coin flip analogy. Ask 1,000 people to flip a coin ten times. Roughly 15 will flip eight or more heads. Are they skilled coin-flippers? Of course not; we expect some extreme outcomes from chance alone. Now imagine those 15 people launch "head-flipping" funds, attract assets based on their "track record," and charge fees for their "skill." That's active fund management in a nutshell.

Kolmogorov's mathematics proves that what looks like skill usually isn't. Random chance produces apparent patterns, hot streaks, and outperformance that feel meaningful but are statistically meaningless. Three to five years of beating the market (the period most investors use to select managers) is mathematically insufficient to conclude anything.

The only rational response is to demand rigorous statistical proof before attributing outperformance to skill. For investors who want to run the numbers themselves to test a manager's claim of skill, the mathematics is unforgiving. And when you apply that standard, the ranks of "skilled" managers collapse to nearly zero.

Myth 4: Short-term Data Tells the Story

Even investors who accept the previous three myths often fall into the fourth trap: using short-term data to make long-term decisions. Three to five years of returns. Morningstar's five-star ratings. Recent performance rankings. This data feels substantial but is mathematically worthless.

Pierre-Simon Laplace, the 18th-century French mathematician, formalized the Central Limit Theorem in his 1812 masterwork Théorie Analytique des Probabilités. The theorem establishes that sample size is everything. Small samples contain enormous variance; large samples reveal true characteristics. For investment returns, you need 30 years minimum, ideally much longer.

The Central Limit Theorem explains why short-term returns are so volatile. A single year's return can be 40% or -35%, seemingly random. But as sample size increases, the distribution of average returns narrows dramatically around the true mean. The range of possible outcomes doesn't disappear; it becomes predictable, quantifiable, and manageable.

Index Fund Advisors maintains nearly 100 years of return data precisely because of this mathematical imperative. Mark Hebner writes in Step 9 of his book: "Statisticians who consider 30 years of risk and return data to be statistically significant would consider this collection of data a feast!"

Why does this matter? Because virtually every active investing decision relies on insufficient data. Fund rating systems average three to five years. Performance tables show one, three, and five-year returns. Investors chase last year's winners.

Laplace's Central Limit Theorem proves that short-term returns tell you almost nothing about long-term expectations. The median return might barely change between five-year and 30-year periods, but the range of outcomes shrinks dramatically. As Hebner explains, "studying the very long-term history better characterizes both the risks and returns of asset classes, empowering investors to make better choices."

The question of how long is long enough becomes critical when evaluating manager performance. The mathematics reveals what short-term data obscures: the handful of five-year winners weren't skilled; they were lucky. Time exposes luck as luck and skill as vanishingly rare.

SPIVA's mid-2025 data reveals persistent active fund underperformance across all timeframes. Over five years, approximately 85-90% of US large-cap funds trail the S&P 500. At ten years, close to nine in ten lag their benchmark. Over 20 years, more than 90% underperform, with survivorship bias making actual investor outcomes even worse. Persistent long-term outperformance remains exceptional.

Morningstar ratings, based on three to five years of risk-adjusted returns, are therefore mathematically not able to provide a valid basis for predicting future performance. They're measuring statistical noise with sample sizes too small to be meaningful.

Laplace proved that you need large samples to distinguish signal from noise. Active investing systematically ignores this proof, building an entire industry on insufficient data. The mathematics condemns this approach as surely as gravity condemns a bridge built on faulty engineering.

Myth 5: Past Winners Keep Winning

The fifth and final myth sounds logical: even if most outperformance is luck (Myth 3), and even if we need long-term data (Myth 4), surely the managers who do demonstrate sustained success will continue succeeding? Past performance might not guarantee future results, but it must predict them somewhat?

Francis Galton, the 19th-century British polymath, discovered a mathematical truth that challenges this assumption: regression to the mean. Extreme outcomes tend to be followed by more moderate outcomes. Tall parents have shorter children on average. Outstanding performance reverts toward mediocrity.

Galton's insight applies powerfully to investment performance. The five-star fund from the past five years is more likely to underperform than repeat its success. The hot manager becomes the cold manager. Yesterday's winners populate tomorrow's laggard lists.

Why? Because markets are competitive. Any legitimate strategy that produces excess returns attracts capital, which arbitrages away the advantage. A fund that genuinely found a profitable pattern will see that pattern disappear as others copy it, flooding the opportunity with capital until returns normalize.

But even without competitive arbitrage, regression to the mean operates independently. If a manager's outperformance included any luck component (and Kolmogorov proved it almost always does) that luck won't persist.

The evidence is compelling. S&P's Persistence Scorecard for Year-End 2024 found that among top-quartile funds within all reported active domestic equity categories as of December 2020, not a single fund remained in the top quartile over the next four years. Zero. Not one fund that was in the top 25% in 2020 remained there for the following four years.

Studies suggest that past fund performance has little to no predictive power for future results. The correlation between past and future returns hovers near zero.

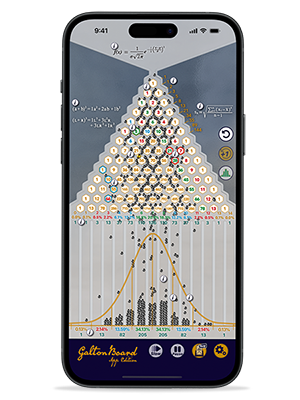

Francis Galton demonstrated this principle using his famous Galton board, a device that physically illustrates how random individual outcomes aggregate into predictable distributions. His work on reversion to the mean remains fundamental to understanding why extreme performance cannot persist.

This raises serious questions about the entire fund selection industry. If you cannot predict which funds will outperform by studying their past performance (Myth 5), and you cannot statistically verify that past outperformance represents skill rather than luck (Myth 3), and you cannot even gather sufficient data to make meaningful distinctions (Myth 4), then the entire exercise of active fund selection collapses.

The mathematics admits no escape. Even if you overcame the daunting challenges posed by Myths 1 through 4 (even if you could identify genuine skill from insufficient data while avoiding timing mistakes and stock-picking delusions) regression to the mean ensures that past winners will not remain winners. Galton proved it in the 19th century. The proof still holds.

Three Centuries, One Verdict

These five myths aren't separate misconceptions; they're one fundamental delusion viewed from five mathematical angles. From Pascal and Fermat in 1654 to Kolmogorov in 1933, probability theory has consistently proven that active investing's core strategies are mathematically unsound.

Markets are extremely difficult to time because short-term outcomes are random (Bernoulli). Stock picking rarely adds value after costs because prices already reflect available information (Pascal/Fermat). Skilled managers are exceptionally hard to identify in advance because apparent outperformance is statistically indistinguishable from luck (Kolmogorov). Short-term data provides insufficient evidence for meaningful decisions because sample sizes are insufficient (Laplace). And even if you somehow overcame all those challenges, past winners are unlikely to remain winners (Galton).

Active investing faces severe structural disadvantages rooted in mathematical principles.

As Mark Hebner notes in his book, "Because news is unpredictable and random by nature, we come to the unavoidable conclusion that movements of stock prices are also unpredictable and random." Yet Hebner also emphasizes that the Galton board sitting in IFA's lobby demonstrates "order in the midst of chaos that is the random walk of Wall Street." That's the paradox probability theory resolves: randomness in the short term, predictability in the long term.

Louis Bachelier, the French mathematician who first applied probability theory to financial markets in 1900, established the mathematical foundation for understanding investing through the lens of randomness. His work, combined with contributions from the mathematicians explored here, provides the intellectual framework for finding order in the chaos of financial markets.

The mathematics has spoken. The verdict came in centuries ago. Active investing often overlooks the implications of probability theory — not because the evidence is ambiguous, but because accepting the proof requires abandoning profitable delusions.

The scholars have done their work. Now investors must do theirs: replace speculation with education, delusion with mathematics, and active management with evidence-based investing. The only question is whether they will accept three centuries of mathematical proof or continue betting against it.

ROBIN POWELL is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the Editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only.

DISCLOSURES:

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice, an offer, or a solicitation to buy or sell any security. Past performance is not indicative of future results. All examples and data cited are based on historical analysis and may not reflect future market conditions. Investing involves risks, including the possible loss of principal. The mathematical principles discussed illustrate theoretical concepts and should not be interpreted as guarantees of investment outcomes. Index Fund Advisors, Inc. (IFA) believes the information to be accurate but does not guarantee its completeness or accuracy. This article was sourced and prepared with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) technology.

For more information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc, please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit www.ifa.com.