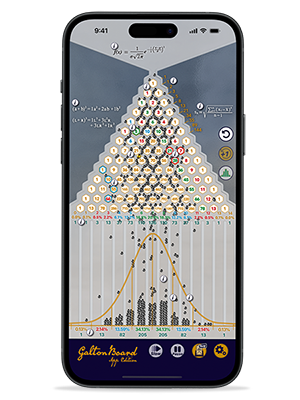

In 1998, IFA Founder and CEO Mark Hebner recognized the addictive nature of gambling while researching the advantages of index funds. He discovered a section on the Gamblers Anonymous website devoted to stock‑market gamblers, revealing how deeply speculation mirrored gambling behavior. This realization led to his award‑winning book Index Funds: The 12‑Step Recovery Program for Active Investors, adopting the recovery‑program framework to help investors break free from compulsive trading. Hebner also observed a striking parallel: casinos worldwide operate 24 hours a day—not because players demand it, but because nonstop access fuels profits and addictive behavior. Today's shift toward near‑continuous trading reflects that same dynamic, making the warnings from decades ago more relevant than ever.

Researchers have developed the first validated diagnostic tool for trading addiction. In its initial test, roughly one in ten amateur traders met the clinical criteria. Meanwhile NYSE and NASDAQ are both pushing to keep markets open nearly around the clock by late 2026.

Every bar in America has a last call. Not because most customers can't handle their drinks. Most can. But public health research showed that unlimited access made problem drinking worse, so states set hours. They built in a forced pause.

The stock market has its own version. The closing bell rings at 4pm Eastern, and trading stops. For all its flaws, that daily shutdown works as a circuit breaker between investors and the pull of watching positions move in real time.

That break is about to disappear. NYSE has received SEC approval to extend trading to 22 hours a day. NASDAQ has filed for 23. Both are targeting late 2026.

The timing isn't great. In March 2025, a research team published the first peer-reviewed scale for diagnosing trading disorder and tested it on 403 amateur traders. Roughly one in ten met the clinical threshold for disordered trading. Nearly a fifth showed at-risk behavior. Treatment centers across the country report rising demand from patients who can't stop.

As we explored last summer, the neurological overlap between active trading and gambling is well documented. But the clinical picture has sharpened since then. New diagnostic tools have emerged. Meanwhile, research shows that less trading time has historically been associated with improved investor returns.

The same research that reveals the problem also points to what has historically worked.

Scientists Can Now Diagnose Trading Addiction, and the Numbers Are Alarming

What does disordered trading actually look like? Coloma-Carmona et al. (2025) mapped how disordered traders behave compared to everyone else. Among those classified as disordered, 12.2% traded daily, versus 1.4% of the non-disordered group. Nearly 39% checked market data every hour or more. Among non-disordered traders, just 3.1% did. And 58.5% of disordered traders independently met the criteria for problem gambling.

Disordered traders weren't placing bigger bets. Their average trade was smaller (around $4,500) than that of at-risk traders ($5,300). They traded more often, in shorter bursts, for less money each time. That pattern mirrors frequent gamblers, who tend to place smaller individual wagers than recreational players. The compulsion isn't about position size. It's about frequency.

The study sample was Spanish, but the behavioral mechanisms — overconfidence, impulsive checking, chasing losses — aren't culture-specific. A systematic review by Loscalzo et al. (2025) examined 23 papers on problematic trading published between 1995 and 2024, spanning the US and Europe. Their finding: the field still hasn't settled on a shared definition. Only four research teams across three decades have proposed treating trading disorder as a distinct diagnosis, rather than shoehorning it into gambling frameworks.

That confusion has real consequences. When clinicians can't agree on what to call something, regulators can't classify it, and patients don't recognize it in themselves.

A case study published last month by Saradha et al. (2026) illustrates the gap. A 29-year-old in India racked up ₹8 million in debt from futures and options trading, scoring 24 out of 27 on the Stock Addiction Inventory. A ten-session behavioral intervention dropped his score to four. He responded to treatment. But he had to find it first, in a specialty clinic, for a condition most doctors have never heard of.

The science is catching up. The infrastructure around it isn't even close.

More Hours, Worse Returns

The clinical picture is alarming. But what does it cost? A November 2024 study offers the clearest answer yet, and it comes not from a psychology lab but from IRS data.

Ed deHaan of Stanford and Andrew Glover of the University of Washington wanted to test a simple question: does having more time to trade make retail investors better off? To find out, they designed a natural experiment using something most of us never think about. Time zones.

US equity markets open at 9:30am Eastern. Someone in California wakes up with fewer hours of market access than someone in New York. Not because of income, education, or investing experience. Just geography.

deHaan and Glover compared households in adjacent counties on opposite sides of time-zone borders. These were people living within miles of each other but with meaningfully different windows of waking trading time. The researchers then tracked their capital gains as reported on tax returns.

The finding was clear. Households with fewer waking hours of market access reported better investment outcomes. Not by a trivial margin.

The study didn't compare reckless traders with disciplined ones. It compared people who were essentially identical except for how many hours they could watch a screen while the market was open. Less time was associated with less trading. Less trading was associated with better results in the sample.

The authors are careful to note limitations. Tax returns capture realized gains and losses, not unrealized positions. The data infers behavior at the county level rather than tracking individual orders. And correlation, even in a strong quasi-experimental design, isn't quite causation. But the directional conclusion lines up with decades of behavioral finance research: on average, more trading activity produces worse outcomes for retail investors.

The exchanges should have to answer an obvious question. If shaving an hour or two off the trading day is associated with meaningfully better returns for ordinary households, what happens when you add 14?

While Scientists Sound the Alarm, the Exchanges Remove the Guardrails

Stock exchanges make money when people trade. More hours mean more volume. More volume means more revenue. That's the business model. And it explains why the clinical evidence on trading addiction, and the economic evidence on trading hours, has had zero visible influence on exchange strategy.

The proposals we flagged earlier are just the beginning. A third venue, 24X National Exchange, has already received preliminary SEC approval for near-continuous trading and aims to go live ahead of the major exchanges. The race isn't toward extended hours. It's toward all of them.

But longer hours are only one layer. The past decade has seen a systematic removal of every friction point that once stood between an investor and an impulsive trade. First, commissions went to zero. Then came fractional shares, turning every stock into a slot machine you could feed with pocket change. Then gamified app design: confetti animations, push notifications, streak rewards. Each step was marketed as democratization. Each step also removed a speed bump that gave investors a moment to reconsider.

The latest escalation makes the trajectory impossible to ignore. Robinhood launched a prediction markets platform in March 2025 and quickly expanded it to include parlay bets on NFL games. The company is reportedly considering election parlays. As Axios noted, Robinhood "is betting on the future of investing being, well, betting."

This isn't a metaphor. Prediction markets use the language of trading (shares, positions, traders) while functioning as sportsbooks. Rabinovitz and Packin (2025) documented how these platforms "employ gamified mechanics and rewards to drive addictive behavior," blurring the line between financial forecasting and outright gambling. When a brokerage lets you parlay NFL games in the same app where you hold your retirement savings, the distinction between investing and gambling isn't blurred. It's gone.

To return to the analogy: this is what it looks like when the pubs lobby to abolish last call. Not because drinkers demanded it, but because the establishments did.

The Gap Nobody Owns

Regulators have tried. The SEC's October 2021 report on the GameStop episode explicitly questioned whether "game-like" brokerage apps were encouraging investors to trade too much. That was the right question. The problem is what came next. Or didn't.

The GameStop frenzy peaked on January 27, 2021, with shares hitting an intraday high of $347.51. By early February, roughly $27 billion in market value had evaporated. Retail investors bore losses that Better Markets estimates at "hundreds of millions, if not billions" in aggregate. And on 01/27/2026, exactly five years later, that same organization published a report documenting how every risk the SEC identified has since spread into crypto, prediction markets, and proposals for round-the-clock trading.

So why hasn't anything happened? The answer isn't indifference. It's a structural mismatch.

The academic community hasn't agreed on what problematic trading is. Without a shared clinical definition, there's no diagnostic framework for regulators to reference. Without a framework, there's no basis for classification. Without classification, there's no clear mandate to act. Each link in that chain depends on the one before it, and the first link is still missing.

The extended-hours proposals tell a similar story. The delays in launching 22-hour and 23-hour trading sessions aren't coming from policymakers raising concerns about investor welfare. They're coming from infrastructure constraints: consolidated data feeds, DTCC and NSCC clearing systems, trade reporting upgrades. The obstacles are logistical. Nobody in the approval process appears to be asking whether addiction risk should factor into the decision at all.

The science, the regulation, and the market structure are all moving forward on separate tracks, at different speeds, with no mechanism to connect them. Clinical researchers can now measure the problem. Exchanges are building the infrastructure to make it worse. And the policy conversation that should sit between those two realities hasn't started.

Building Your Own Last Call

If the exchanges won't maintain a closing bell, investors need to build their own. The most effective way to do that isn't willpower. It's structure.

Trading addiction feeds on decision points. Every choice to buy, sell, check, or adjust is a potential trigger. Fewer decisions lead to better results.

Evidence-based investing works on the same principle. Not by limiting when you can trade, but by eliminating the reasons to. A globally diversified index portfolio doesn't require you to pick stocks, time markets, or monitor positions throughout the day. There's no daily decision to make. No trigger to pull. The strategy runs whether the market closes at 4pm or never closes at all.

When round-the-clock trading arrives, the investors most at risk won't be those with bad strategies. They'll be those with no strategy, the ones making ad hoc decisions in response to price movements, headlines, and push notifications at 2am. A written investment plan with a predetermined rebalancing schedule can help reduce those decision points before they arise.

None of this guarantees superior returns. Markets are unpredictable, and every approach carries risk. But the behavioral evidence points in one direction: reducing discretionary trading has historically improved outcomes for the average retail investor. A fee-only fiduciary advisor, one with no incentive to generate trades, can help build and maintain that kind of framework.

The exchanges are building a market that never sleeps. The rational response is a portfolio that doesn't need to stay awake.

What to Do if You Think You Have a Problem

So what can you do if you recognize yourself in any of these patterns?

Count your trades. The Coloma-Carmona data gives a baseline: disordered traders were nine times more likely to trade daily than everyone else. If you're trading multiple times a month without a documented reason for each one, that's a signal worth paying attention to.

Turn off every brokerage notification on your phone. All of them. Price alerts, earnings announcements, trending tickers. Each one is a prompt to act, and most actions hurt.

Separate speculation from investment. If you enjoy trading, put a fixed amount in a standalone account. Keep it away from your retirement savings. Losing 100% of a $5,000 play account is a bad month. Losing 10% of a $500,000 retirement portfolio can represent a decade.

Talk to someone. If any of the patterns described in this article feel familiar, contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357. It's free, confidential, and available 24/7.

Conclusion

Last call was never meant to punish responsible drinkers. It exists because unlimited access produces predictable harm in a predictable minority, and the cost spreads to everyone around them. The evidence on trading now suggests the same thing, with clinical precision. Researchers can identify who's at risk. Economists can measure what it costs. Clinicians can treat it. The science has done its part.

The regulatory response hasn't kept pace, and there's no sign it will before 22-hour trading goes live. Until it does, the most effective protection is a plan that doesn't ask you to make decisions in real time, one that works identically whether markets close at 4pm or never close at all.

The closing bell is disappearing. A good investment plan means you never needed it.

Resources

Coloma-Carmona, A., Carballo, J. L., Miró-Llinares, F., Aguerri, J. C., & Griffiths, M. D. (2025). Development and validation of the Trading Disorder Scale for assessing problematic trading behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 14(2), 941–958.

Loscalzo, Y., Rogier, G., & Velotti, P. (2025). Problematic trading: A systematic review of theoretical considerations. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1505012.

Saradha, S., Kumar, R., & Sharma, M. K. (2026). A multimodal approach to addictive-like behavior in stock trading: A case report. Cureus, 18(1), e101490.

deHaan, E., & Glover, A. (2024). Market access and retail investment performance. The Accounting Review, 99(6), 101–127.

Rabinovitz, S., & Packin, N. G. (2025). All bets are on: Addiction, prediction, regulation, and the future of financial gambling. Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal, 36(1), 90.

Better Markets. (01/27/2026). Five years after GameStop, crypto, prediction markets, and 24/7 trading make meme stocks the least of retail investors' troubles.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (10/14/2021). Staff report on equity and options market structure conditions in early 2021.

Further Reading

The connection between stock trading and addictive behavior isn't a new observation. IFA founder Mark Hebner has been warning about it for years. In Step 1 of his award-winning book, Index Funds: The 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors, he explores the parallels in detail and lays out what a healthier relationship with investing actually looks like. You can read or listen to Step 1 here.

ROBIN POWELL is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the Editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only.

DISCLOSURES:

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice, an offer, or a solicitation to buy or sell any security. Past performance is not indicative of future results. All examples and data cited are based on historical analysis and may not reflect future market conditions. Investing involves risks, including the possible loss of principal. The mathematical principles discussed illustrate theoretical concepts and should not be interpreted as guarantees of investment outcomes.

Index Fund Advisors, Inc. (IFA) believes the information to be accurate but does not guarantee its completeness or accuracy. This article was sourced and prepared with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) technology.

For more information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc, please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit www.ifa.com.