When Eugene F. Fama published "Random Walks in Stock Market Prices" (1965), he crystallized a powerful idea: because new information arrives unpredictably and is rapidly embedded in prices, short-term price changes are largely unpredictable. The practical implication is stark: stock-picking and market timing—two sides of the same predictive coin—are unlikely to deliver reliable, risk-adjusted outperformance after costs. This insight matured into the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), spurred the creation and adoption of index funds, informed the Fama–French asset-pricing models, and culminated in Fama's 2013 Nobel Prize. Dr. Fama continues to do research and his fulfil his role as a finance professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

The real-world evidence on active management from both academia, industry and practitioners is consistent and cumulative: most active strategies—whether expressed as stock selection or market-timing—fail to beat low-cost benchmarks over time; investor attempts to jump in and out often miss a handful of the market's best days, compounding underperformance. That's why today's best practices for investing emphasizes risk capacity determination, broad diversification of risk exposures, low costs, low taxes and disciplined risk maintenance through rebalancing. Finally, avoid all forms of active management. These are the core concepts of evidence-based investing and of IFA's educational mission to change the way the world invests.

What Fama argued—and why it undermines stock-picking and market timing

In 1965, Fama explained in plain language that if successive price changes are independent of each other and reflect information quickly, then charting/technical analysis and pattern-based prediction should fail on average; likewise, fundamental analysis must overcome mistakes, fierce competition, taxes and fees to add value. Put simply, you cannot reliably forecast short-run price moves, which undercuts both stock-picking (choosing winners ahead of time) and market timing (shifting in/out before the market changes direction). His more technical companion paper, "The Behavior of Stock-Market Prices," supported these points with data. In his landmark 1970 paper, "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work," Fama defined and structured the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), fundamentally changing the field of financial economics. Fama's review synthesized existing theories and empirical evidence to propose that in an efficient market, asset prices reflect all available information.

Fama's 1991 update, "Efficient Capital Markets: II", made an economically sensible refinement: prices reflect information to the point where the marginal benefit of trading no longer exceeds the marginal cost. That doesn't assert perfection—it says exploitable predictability, net of costs, is rare. As a corollary, strategies that depend on timely entry/exit calls on broad markets (market timing) or selecting under or over priced securities which means buying future outperformers and selling future underperformers (stock picking) face daunting odds. If there are no mispriced markets or securities, neither strategy should work and that is what the empirical research has concluded.

Evidence, challenges, and how the theory evolved

Critiques and complementary evidence enriched the research program without overturning its investment message:

Departures from a pure random walk: Lo & MacKinlay (1988) rejected the strict random-walk model for weekly returns—especially among small caps—using variance-ratio tests. Their findings reveal some predictability in return autocorrelations, but not a free lunch after costs.

Momentum at 3–12 months: Jegadeesh & Titman (1993) documented that recent winners tend to beat recent losers over the next 3–12 months (momentum). The effect persisted in later samples, raising modeling questions even as it remains difficult to time net of trading frictions and taxes. According to this paper from the University at Albany, "Momentum: Evidence and Insights 30 Years Late", the strength and consistency of the momentum effect have varied over time, with some sub-periods showing stronger results and others showing weaker or even statistically insignificant average profits.

Excess volatility and long-horizon predictability: Shiller (1981) argued prices fluctuate more than subsequent dividends justify, consistent with time-varying expected returns. The Nobel committee recognized both short-run unpredictability (Fama) and long-run variation (Shiller).

Fama's response was to improve the model of expected returns, not to abandon efficiency.

With Kenneth French, he introduced the three-factor model (market, size, value) and later the five-factor model (adding profitability and investment), which better describe return differences across diversified portfolios—even as momentum remains a distinct, debated dimension.

From ideas to implementation: indexing beats picking and timing over longer periods of time

Index funds are the practical offspring of random walk/EMH logic:

Institutional genesis (1971): John "Mac" McQuown's team, including Dimensional Fund Advisors Co-Founder David Booth, at Wells Fargo built one of the first equity index portfolios for Samsonite's pension plan—proof that rules-based, low-cost exposure could replace guesswork.

Retail breakthrough (1976): John C. Bogle launched the First Index Investment Trust (now Vanguard 500 Index Fund), taking indexing mainstream for individual investors.

Why it stuck: Long-horizon scorecards (SPIVA; Morningstar's Active/Passive Barometer) show that most active funds underperformed their benchmarks over 10–20 years—because mistakes in selections, higher fees, trading costs, taxes, and inconsistent decisions overwhelm any ephemeral edge.

Why market timing underperforms in practice

Even if you don't pick stocks, you might try to time stocks, bonds, or "the market." The evidence warns against it:

Missing just a few "best days." Many of the best single days cluster near the worst days, making re-entry timing nearly impossible. Studies show that being out of the market for only 10–20 of the best days over decades can slash long-term returns—precisely because rebounds often follow drawdowns.

Behavioral timing costs (DALBAR). Decades of the DALBAR QAIB reports document that the average equity investor lags market benchmarks materially, largely due to buy high/sell low behavior—i.e., poor timing of inflows/outflows. The 2025 report again found a large gap between investor returns and the S&P 500's results in 2024 due to mistimed exits/entries.

Tactical-allocation funds' record. Morningstar's recent review shows tactical-allocation funds (which explicitly time asset-class exposure) lagged both simple 60/40 portfolios and category peers over 5–20 years—often with higher volatility to boot.

Policy views. Vanguard's research underscores why strategic (policy) asset allocation with rebalancing is more dependable than tactical shifts based on short-term forecasts: successful timing is "easier said than done" and adds active risk that seldom pays.

Alongside indexing, Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) took a sister path: rather than "tracking an well-known commercial index" precisely (which can invite costly, predictable trades), systematically target well-researched dimensions or factors representing academic style indexes (like size, value, profitability) across global markets while controlling costs and reducing trading frictions—a way to harness persistent drivers of higher expected returns without picking stocks or timing markets.

Nobel recognition—and its meaning for investors

The 2013 Nobel Prize honored Fama, Hansen, and Shiller for empirical analysis of asset prices: Fama demonstrated short-run unpredictability and rapid incorporation of information; Shiller showed long-run predictability and excess volatility; Hansen provided tools (GMM) to test pricing models. The overarching message: markets are not perfectly predictable, but the burden of proof is on those claiming persistent outperformance—especially through stock-picking or timing.

"Tune Out the Noise"—and IFA's role in the story

The 2024–2025 documentary "Tune Out the Noise," directed by Errol Morris, tells how finance became a science—profiling Fama, French, Booth, and IFA's Mark Hebner, among others. It connects the dots from academic breakthroughs to index funds and client-focused advice. IFA hosts the full film and resources in IFA.com and their App for investors seeking to convert insight into action.

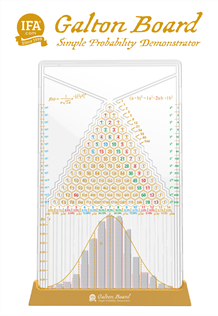

Applying the ideas: The IFA MarketCoin—a tactile lesson in randomness and the futility of timing

Why a coin? Because a flip captures what the data say: short-term returns are dominated by news shocks—i.e., randomness. MarketCoin turns that abstraction into an experience:

Flips with a positive drift. Each flip of the market in various periods (day, month or year) reflects new and random information that moved the prices of securities. Add a positive drift per period, like the median return for days, months or years, to reflect the long-run equity and other factor premiums: over time expected returns are positive even though changes are random relative to the median return. This makes explicit why "random walk" ≠ zero expected return and why forecasting is only as good as a coin flip. See the table below:

Investor playbook—what Fama's legacy means for your portfolio

Own the market(s), don't predict them. Use broad index funds or systematic multifactor strategies to capture reliable drivers of returns at low cost. Avoid stock-picking and market timing.

Stay invested and rebalance. Because the best days cluster near worst days, jumping out risks missing disproportionate gains. A rules-based rebalancing policy is superior to ad-hoc timing.

Beware the performance-chasing trap. Long-run scorecards show low success rates for active funds; DALBAR's QAIB shows investor timing is the bigger enemy. Build a policy portfolio you can stick with.

Prefer strategic over tactical allocation. Vanguard's research and Morningstar's fund results echo the same point: tactical shifts rarely improve risk-adjusted outcomes.

Why the debate endures—and why the conclusion doesn't change.

Short-run unpredictability (Fama), long-run variation in expected returns (Shiller), and rigorous testing (Hansen) coexist. But the investment counsel—borne out by history—hasn't changed since 1965: don't pick, don't time. Diversify, minimize costs, rebalance, and tune out the noise.

Further viewing & reading

- Tune Out the Noise (Documentary): trailer and full film—profiles Fama, French, Booth, Hebner; hosted on IFA.com

- Fama, "Random Walks in Stock Market Prices" (1965); "Efficient Capital Markets" (1970); "Efficient Markets: II" (1991).

- Fama & French, three-factor (1993) and five-factor (2015) models.

- Shiller, "Do Stock Prices Move Too Much…?" (1981).

- SPIVA / Morningstar Active-Passive scorecards; DALBAR QAIB for investor-timing evidence; Vanguard on tactical vs. strategic allocation.

Citations (selected)

Fama (1965/1970/1991), Fama–French (1993/2015), Shiller (1981), Lo & MacKinlay (1988), Jegadeesh & Titman (1993), Nobel Prize (2013), Wells Fargo / Vanguard indexing history, SPIVA & Morningstar active vs. passive data, DALBAR QAIB, Dimensional/IFA resources, missed-best-days analyses, Vanguard research on tactical allocation.

Disclosure:

This is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, product, or service. This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute personalized investment advice. Performance results referenced reflect historical and academic analyses and are not indicative of future outcomes. Past data is net of certain costs but should not be construed as representative due to varying fees, expenses, and unpredictable market conditions. Momentum strategies, for example, are subject to sub-period volatility which may produce inconsistent results.

All investments carry risks, including the potential loss of principal. The article references empirical research from academia and industry. While foundational principles of diversification and low costs are illustrated with real-world results, outcomes depend heavily on economic conditions, trading environments, and individual circumstances. We recommend consulting a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions to ensure alignment with personal financial goals, risk tolerance, and circumstances.

For full compliance discussion and detailed services information about IFA, including our adherence to SEC Marketing Rule 206(4)-1 standards, compensation, and potential conflicts of interest, please visit www.adviserinfo.sec.gov and our firm brochure at www.ifa.com.