April 2025 was a turbulent month for the financial markets. Global stock prices plunged sharply following President Trump's "Independence Day" tariff announcement on April 2, and volatility surged as markets struggled to navigate a flood of conflicting economic data and geopolitical tensions. Once again, investors were tempted to predict the next market move in hopes of maximizing gains or minimizing losses.

From a behavioral standpoint, the urge to "time the market" during such turbulent times is both natural and understandable. Loss aversion triggers strong emotional reactions to falling prices, while overconfidence and the illusion of control lead many to believe they can predict or influence market movements. Recency bias only adds pressure by making recent trends appear as reliable signals.

In early April, numerous market analysts sounded alarms of potentially worse to come. For instance, Torsten Slok of Apollo Global Management placed the probability of a U.S. recession at 90%, while Cem Karsan from Kai Volatility forecasted a 40% stock market drop.

Several respected commentators warned that the unprecedented tariff crisis and threat of a global trade war meant traditional investing rules no longer applied.

Of course, no one can predict the future with certainty. There may well be further steep declines in the weeks and months ahead. Yet, at the time of writing, the U.S. market has rebounded fully from the April 2 sell-off, with other global markets performing even better.

No doubt some investors profited amid the chaos. However, many others only worsened their outcomes by reducing equity exposure after the initial downturn.

So, what lessons can this episode teach us about relying on expert opinions during volatile markets?

True, a few experts predicted a quick recovery, but most did not. How often do experts get it wrong? The truth is, it happens frequently.

The Evidence on Forecasters is Mixed

One of the most comprehensive studies, conducted by CXO Advisory in 2012, analyzed over 6,500 predictions from 68 prominent U.S. market commentators between 1998 and 2012. The results were striking: their average accuracy over this period was 47% — no better than random chance. Even those who seemed more accurate often made too few predictions to be statistically significant. The study also revealed many forecasters tended to follow market trends or echo prevailing sentiment rather than provide truly independent insights. While certain forecasters seemed to succeed in specific short term circumstances, broader research highlights the difficulty of consistently outperforming markets.

A follow-up study in 2019 by Bailey, Borwein, Salehipour, and Lopez de Prado revisited the data using a more rigorous scoring system that rewarded clear, long-term forecasts while penalizing vague or short-term ones. The findings were even bleaker: most experts hovered near coin-flip accuracy. A small handful stood out with consistent success, but the overwhelming conclusion remained: market gurus as a group are no better than guessing.

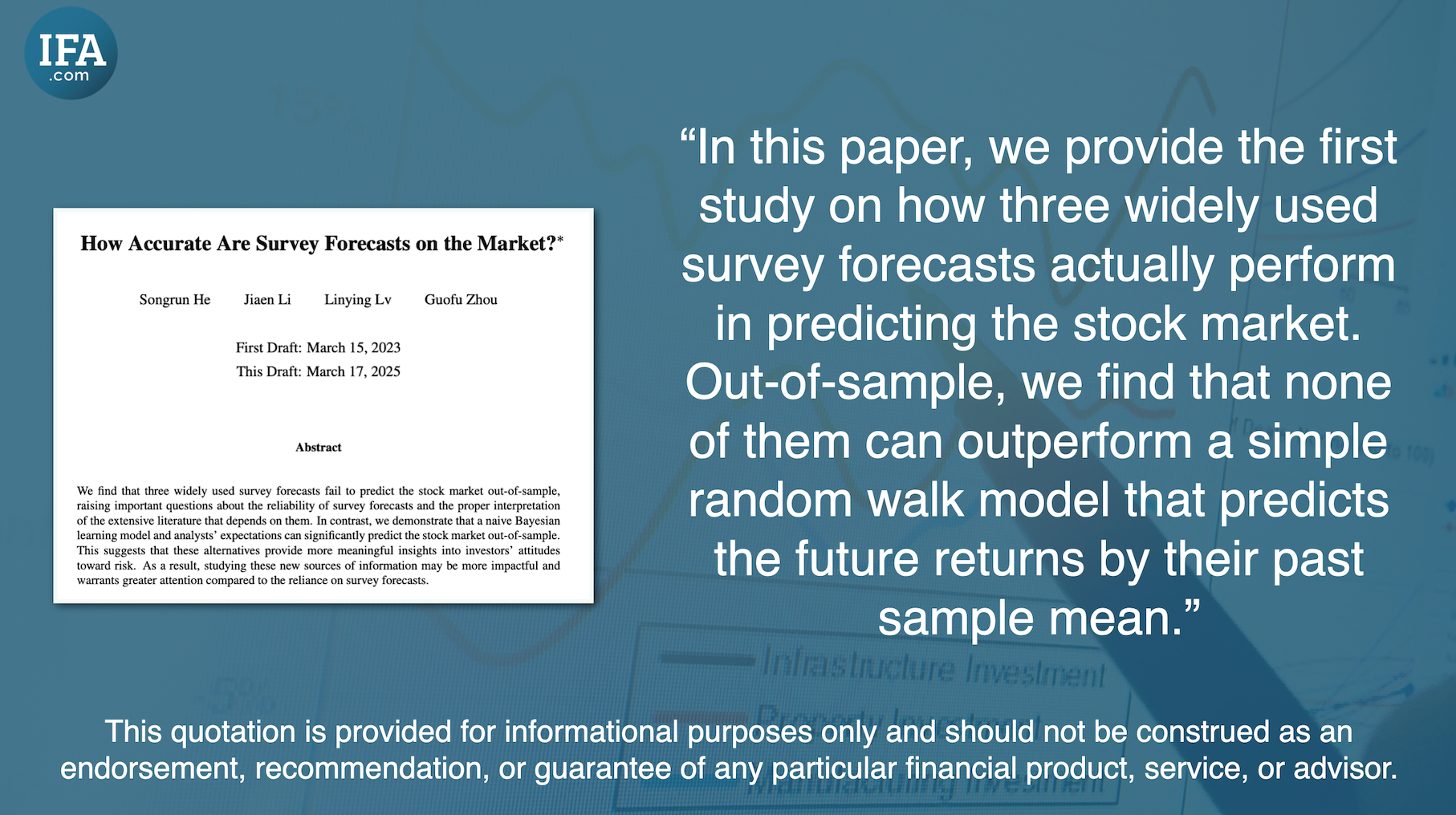

A third study, by He, Li, Lv, and Zhou in 2023 (updated March 2025), examined widely used survey forecasts, including those from households, CFOs, and professional economists. They found these surveys predicted future stock returns no better than assuming markets would continue at their historical average. In some cases, forecasts were misleading, underestimating risk and painting an overly optimistic picture. Interestingly, these surveys were more accurate forecasting economic indicators like GDP or inflation but consistently failed at forecasting stock returns.

The message from all three studies is unequivocal: whether it's a TV pundit or professional survey, stock market predictions are rarely reliable. Investors are generally better off tuning out the noise and focusing on robust, evidence-based strategies such as diversification and long-term investing.

Let's be clear: market forecasters and financial media contributors are not unintelligent. Most are highly knowledgeable, and their arguments often seem plausible.

Why Market Forecasting is so Difficult

So why is their ability to accurately predict market movements so limited?

There are two main reasons. First, as Yogi Berra is once supposed to have quipped, "It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future." Economic forecasting alone is notoriously hit-and-miss. Market experts must also anticipate political and geopolitical events, and then predict how markets will react, which is a whole new level of complexity.

Second, the collective wisdom of the financial markets surpasses the insights of any individual. Markets incorporate all known information at any moment, and prices adjust within seconds when new information emerges. Unless you have privileged information — for example, as an economic advisor to the President — it's highly unlikely you possess a meaningful edge. And trading on inside information carries serious legal consequences.

Rex Sinquefield, a pioneer of index funds and co-founder of Dimensional Fund Advisors, described the market as a "collective brain." In an early IFA video interview, Sinquefield said investors should "think of the system of market prices as a vast processing machine that aggregates all information. One individual might know a bit more than others, but can anyone know more than six billion people combined? No. Each person knows only a tiny fraction of what is knowable and built into prices."

Market Timers Must Be Right, Again and Again

Identifying a market turning point — the exact start of a fall or recovery — is extremely challenging. But being right once isn't enough. Nobel laureate William Sharpe studied this in a 1975 paper and found a market timer needs to be correct 74% of the time just to match a passive strategy with similar risk. A 1992 follow-up by SEI Corporation estimated required accuracy between 69% and 91%.

How do actual market gurus perform? According to CXO Advisory, a review of 28 high-profile market timers from 2000 to 2012 found that none consistenty met Sharpe's threshold of accuracy after accounting for costs. Most were right less than half the time. However, outcomes may vary depending on the time period studied, the methods usedd, and individual circumstances.

Even those correct more than half the time fell short after accounting for costs. Timing exits and entries perfectly is costly, and transaction fees, taxes, and human error further reduce chances of success.

Market Timing Proved to be a Losing Strategy Yet Again

In short, market timing strategies faced significant challenges during last month's turmoil, as they often do in volatile markets.

If you tuned out the noise and stayed invested, you deserve congratulations. But if you sold in panic or nearly did, treat it as a learning experience.

Markets will undoubtedly experience sharp declines again. It's only a matter of time. To stay the course, you need a robust financial plan and an evidence-based advisor to rely on whenever you're tempted to act irrationally.

Meanwhile, if you want to learn more about the futility of trying to time the market, I highly recommend Step 4 of Mark Hebner's award-winning book, Index Funds: The 12-step recovery program for active investors. You can read or listen to it here free of charge.

ROBIN POWELL is the Creative Director at Index Fund Advisors (IFA). He is also a financial journalist and the Editor of The Evidence-Based Investor. This article reflects IFA's investment philosophy and is intended for informational purposes only.

This article is intended to provide general educational insights into market behavior and investment strategies during periods of volatility. All investment strategies, including evidence-based or passive investing approaches, involve risks, including potential underperformance in specific markets or time frames. It does not constitute financial or investment advice and should not be relied upon in making financial decisions. Readers are encouraged to consult with a qualified Investment Advisor to create a personalized investment plan based on their individual financial needs and circumstances.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and reflects the perspective of Index Fund Advisors (IFA), with which the author is affiliated. It should not be interpreted as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any specific security, product, or service. Readers are encouraged to consult with a qualified Investment Advisor for personalized guidance. Please note that there are no guarantees that any investment strategies will be successful, and all investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. This article references third-party studies. While these findings have been reported accurately, they are not exhaustive, and results may vary depending on time frame or methodology. Investors should consider consulting recent research to make informed decisions.

Quotes and images included are for illustrative purposes only and should not be considered as endorsements, recommendations, or guarantees of any particular financial product, service, or advisor. IFA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of third-party content. For those seeking additional insights into the challenges of market timing, Step 4 of Mark Hebner's award-winning book ‘Index Funds: The 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors' offers a detailed perspective. This book is available free of charge here. References to third-party resources, including books, are informational and do not constitute endorsements or solicitations. IFA does not receive compensation related to this recommendation

For additional information about Index Fund Advisors, Inc., please review our brochure at https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/ or visit our website at www.ifa.com.